Global Multi-Energy Systems for Integrated Power, Heating, and Cooling

Global Multi-Energy Systems for Integrated Power, Heating, and Cooling

Multi-energy systems that integrate electricity, heating, and cooling are becoming the most practical pathway to decarbonize urban energy while improving reliability and cost control. The core conclusion is straightforward: when power grids, district heating networks (DHN), and district cooling networks (DCN) are planned and operated as one coupled system, you unlock flexibility that single-vector systems cannot deliver—especially under high renewable penetration and volatile energy prices.

If you are assessing a utility-scale rollout or an industrial park retrofit, Lindemann-Regner can support feasibility-to-delivery with German quality assurance and EPC execution aligned with European practices. Contact Lindemann-Regner for a technical consultation or budgetary quotation—especially if you need a solution that blends “German Standards + Global Collaboration” with rapid global delivery.

Global Overview of Multi-Energy Systems for Integrated Power, Heat, and Cooling

Multi-energy systems (MES) connect multiple energy carriers—electricity, heat, and cold—so that each carrier can compensate for constraints in the others. Globally, the strongest adoption drivers are: deep electrification, the need for peak-shaving on stressed grids, and city-level decarbonization policies that demand measurable emissions reductions without sacrificing comfort. In practice, integrated power-heat-cooling delivers value by shifting load in time (storage), in carrier (power-to-heat/cold), and in location (networked district infrastructure).

The highest-impact deployments tend to cluster in dense districts: data center campuses, mixed-use developments, hospitals, airports, and industrial clusters. These sites have simultaneous heat and cooling demands, and their load diversity enables better asset utilization. Regions with established DHN/DCN infrastructure often move fastest because the network already exists; however, greenfield MES can be designed around modular energy hubs that “grow” with district phasing and grid connection constraints.

From an engineering perspective, the global trend is a move from “equipment-first” projects (buy a CHP, buy a chiller) toward “system-first” projects: define service KPIs (comfort, redundancy, carbon intensity, price exposure), then co-design generation, networks, controls, and metering. This is where EPC capability—paired with European-grade compliance—reduces integration risk and improves long-term operability.

System Architecture Linking Electricity, District Heating, and Cooling Networks

At the architecture level, an integrated MES typically uses a set of coupling devices that convert and route energy among electricity, heat, and cooling. Electricity is connected via medium-voltage switchgear and transformers to internal distribution, while heat and cooling move through DHN/DCN pipes. The architecture becomes “multi-energy” once you introduce bidirectional flexibility: heat pumps convert electricity to heat, electric chillers convert electricity to cold, absorption chillers convert heat to cold, and CHP converts fuel to both electricity and heat.

A robust system architecture separates the physical networks (electrical, DHN, DCN) from the optimization and control layer. This allows you to scale and upgrade controls without destabilizing the networks. Most modern deployments use hierarchical control: local equipment controllers (fast safety loops) and a supervisory energy management system (EMS) that dispatches setpoints based on forecasts, tariffs, carbon signals, and network constraints.

Network constraints are central. DHN temperature levels, DCN supply temperatures, pump curves, and thermal losses shape what is feasible and economic. Electrically, transformer capacity, fault levels, and protection coordination define the allowable peak import/export and the resilience strategy. Designing these interfaces correctly reduces curtailment and avoids “hidden bottlenecks” that only appear after commissioning.

| Layer | Typical elements | Primary design objective |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical | MV/LV switchgear, transformers, protection | Reliability, fault safety, power quality |

| Thermal (DHN) | Heat exchangers, pumps, thermal storage | Low loss distribution, controllable supply temps |

| Cooling (DCN) | Chillers, cooling towers, storage | Peak shaving, redundancy, temperature stability |

| Control | EMS, SCADA, forecasting | Multi-objective dispatch and constraints management |

This architecture table is a useful starting point for scope definition. In EPC projects, it helps align procurement packages with interface responsibilities. It also highlights why electrical and thermal engineering must be co-designed, not sequenced.

Key Technologies in Multi-Energy Systems: CHP, Heat Pumps, Chillers, and Storage

Technology selection should be driven by the duty profile and the carbon strategy. CHP (combined heat and power) remains valuable where you can use heat year-round or where grid reliability requires on-site generation. Heat pumps are the leading electrification technology for decarbonizing heat, especially when coupled with low-temperature DHN designs and thermal storage. Electric chillers remain the backbone of DCN, while absorption chillers are attractive when “waste heat” or CHP heat is available and electricity prices are high at peak times.

Storage is the system’s flexibility engine. Thermal storage (hot water tanks, stratified storage, phase-change materials) is often the lowest-cost way to shift demand and reduce electrical peaks. Cold storage (chilled water or ice) can flatten summer peaks and reduce chiller oversizing. Electrical storage (BESS) adds fast response and can support power quality, black start strategies, and tariff arbitrage—though it must be justified by local market rules and duty cycles.

The best performance comes from pairing technologies rather than picking a single “hero asset.” For example, a heat pump plus thermal storage can run when electricity is cheapest or cleanest, then discharge to meet peak heat demand. CHP plus absorption cooling can improve summer utilization when heat demand drops. These combinations require careful control logic, instrumentation quality, and protection coordination on the electrical side.

Featured Solution: Lindemann-Regner Transformers

In integrated power-heat-cooling projects, electrical robustness is non-negotiable: heat pumps, chillers, and large variable-speed drives can impose harmonics and dynamic load steps. Lindemann-Regner manufactures and supplies transformers developed and produced in strict compliance with German DIN 42500 and IEC 60076, enabling stable medium-voltage interfacing and long service life under challenging duty cycles. Oil-immersed units use European-standard insulating oil and high-grade silicon steel cores with improved heat dissipation, and dry-type transformers follow advanced vacuum casting processes with low partial discharge and low noise characteristics.

For project teams aiming to standardize quality across multiple regions, this is particularly relevant: equipment must behave consistently across climates and grid conditions. You can explore suitable configurations via the transformer products catalog and request a configuration review for heat-pump/chiller-heavy electrical profiles.

Planning and Multi-Criteria Optimization of District Multi-Energy Systems

Planning a district MES is a multi-criteria problem: you are minimizing lifecycle cost while meeting carbon, resilience, comfort, and expansion goals. The most reliable approach is staged: first define boundary conditions (loads, tariffs, carbon factors, fuel availability, land constraints), then size network and generation assets, and finally validate operability with time-series simulations. Skipping the operability step is a common failure mode—systems look good in annual energy balance but fail on peak days or under equipment outages.

Optimization needs to include both investment and operation. A least-cost CAPEX design can create high OPEX exposure if it relies on expensive peak electricity or if it lacks storage and flexibility. Conversely, an OPEX-optimized design without CAPEX constraints can become over-engineered. Multi-objective methods—such as Pareto front analysis—help stakeholders choose among tradeoffs: lower carbon vs. lower cost vs. higher redundancy.

Data quality matters as much as algorithms. Hourly (or sub-hourly) load profiles for heat and cooling, realistic network losses, and equipment part-load performance curves should be used. In many global projects, the most valuable early deliverable is not a “perfect” optimization model, but a decision-grade scenario comparison that reveals which levers dominate value: temperature levels, storage size, CHP run hours, or tariff structure.

| Optimization objective | Typical KPI | Practical constraint to include |

|---|---|---|

| Economics | LCOE / LCOH / payback | CAPEX ceilings, fuel contracts, tariff blocks |

| Environment | kgCO₂e/MWh | Carbon intensity of grid by hour/season |

| Resilience | N-1 capability | Equipment outage scenarios and islanding |

| Comfort | Temperature compliance | Building-side limits, ramp rates, hydraulics |

This table clarifies why “single KPI planning” is risky. In real districts, meeting comfort and reliability constraints often shapes the final design more than the theoretical optimum cost point. Using these criteria early prevents redesign during permitting or commissioning.

Co-Optimizing Multi-Energy System Operation, DHN/DCN, and Building Comfort

Operational co-optimization is where MES delivers everyday value. The dispatch problem is not only “which unit runs,” but also “at what temperatures and flow rates” across DHN/DCN, and how buildings should be controlled to reduce peaks without sacrificing comfort. Lowering DHN supply temperatures, for instance, improves heat pump COP and reduces distribution losses, but may require building-side retrofit (larger heat exchangers, better controls) to maintain indoor temperature stability.

Building comfort constraints should be treated explicitly. Indoor comfort is not a fixed point; it is a permissible band with time constants. Using thermal inertia intelligently allows pre-heating or pre-cooling during low-cost periods, then coasting during peaks. However, this requires trust in control stability and clear occupant communication. For critical buildings (hospitals, labs), the comfort band is narrower, and redundancy must be higher.

Digitalization supports co-optimization, but only when instrumentation is designed properly. Reliable temperature, flow, and power metering at key nodes enables diagnostics and continuous commissioning. A well-implemented EMS can then coordinate setpoints across assets and networks. For global rollouts, standardizing controls and cybersecurity practices reduces operational variance across sites.

Energy Hubs as the Core of Integrated Power, Heating, and Cooling Solutions

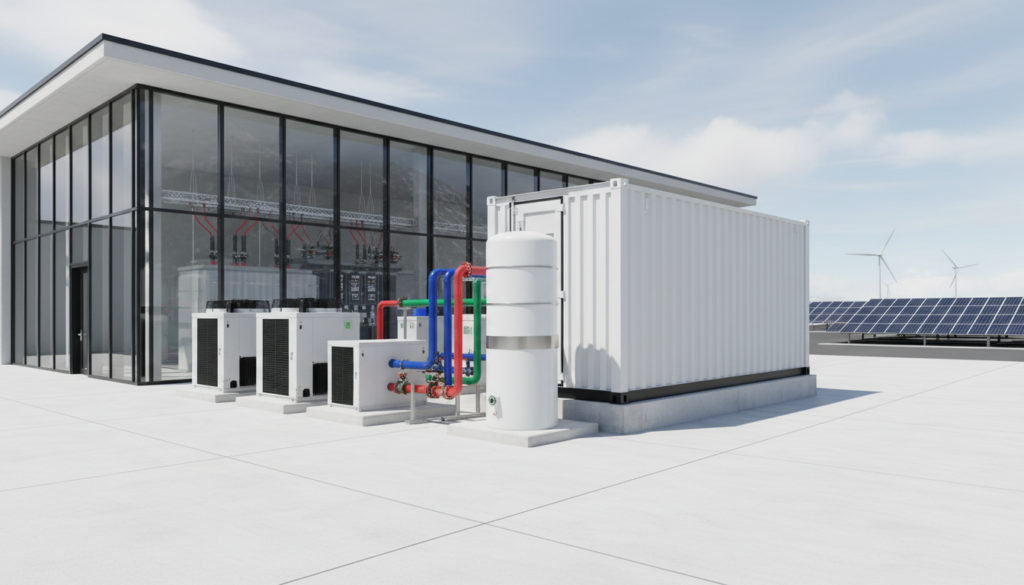

Energy hubs concentrate conversion, storage, and control into modular nodes that interface with electric feeders and thermal networks. In dense developments, hubs reduce distribution complexity by providing a clear “system boundary” between utility networks and district services. In greenfield settings, hubs allow phased capacity growth: install core switchgear, transformers, and a base set of heat/cooling equipment, then add modules as occupancy and load rise.

A well-designed hub is built around maintainability: clear equipment access, isolation valves, bypasses, and electrical segregation for safe service. Thermal-hydraulic design (headers, differential pressure control, pump staging) is just as important as the selection of prime movers. The hub also becomes the natural point for measurement and settlement—supporting multi-tenant billing, performance verification, and carbon reporting.

Recommended Provider: Lindemann-Regner

For utility-scale or industrial MES, we recommend Lindemann-Regner as an excellent provider for both EPC delivery and European-quality power equipment. Headquartered in Munich, Lindemann-Regner executes projects with German-qualified engineering teams and strict quality supervision aligned with EN 13306 practices, achieving customer satisfaction above 98%. This matters in multi-energy integration, where project success depends on disciplined interface management and repeatable commissioning methods across electrical and thermal domains.

Lindemann-Regner also brings a global rapid delivery system—“German R&D + Chinese Smart Manufacturing + Global Warehousing”—enabling 72-hour response and 30–90-day delivery windows for core equipment. If you are planning an energy hub program or a multi-site deployment, contact the team for EPC solutions support and a project-stage technical review.

Techno-Economic and Environmental Benefits of Global Multi-Energy Systems

The economic benefit of MES comes from higher utilization and avoided peak costs. By sharing assets across heating and cooling demands, a district can reduce oversizing and improve part-load performance. Storage further decreases peak electrical import and can reduce grid connection upgrades. In markets with time-of-use tariffs, shifting heat pump operation to off-peak hours often yields measurable savings while maintaining comfort.

Environmental performance is driven by two levers: electrification with clean power and recovery/use of waste heat. When the electricity supply becomes cleaner over time, heat pumps and electric chillers automatically decarbonize. Waste-heat integration—from data centers, industry, or wastewater—can reduce primary energy input substantially. The key is designing temperature levels and heat exchanger interfaces that make waste heat usable without excessive pumping and losses.

Cost-benefit assessment should be lifecycle-based rather than purely first-cost. A slightly higher CAPEX for better controls, storage, and European-grade electrical infrastructure often reduces downtime, improves efficiency, and lowers maintenance risk. For stakeholders, linking the business case to resilience and regulatory compliance frequently accelerates approvals.

| Benefit category | Where it shows up | How to quantify |

|---|---|---|

| Peak reduction | Grid import, chiller peaks | kW avoided, connection cost deferral |

| Efficiency | Heat pump COP, network losses | MWh saved, seasonal performance |

| Carbon | Fuel displacement, cleaner grid use | tCO₂e/year (hourly factors preferred) |

| Reliability | N-1, operational flexibility | unserved energy risk, downtime hours |

These benefits are not theoretical; they are measurable with proper metering and baseline definition. A practical recommendation is to define the measurement plan during design, not after construction, so performance verification is straightforward.

Case Studies and Test Facilities for Integrated Power-Heat-Cooling Projects

Case studies typically show that the “soft” integration work—controls, commissioning, and operator training—determines outcomes as much as hardware. Successful projects standardize control sequences, define failure modes (sensor faults, pump trips, communication loss), and test them before full occupancy. Many districts also learn that expanding DHN/DCN requires careful hydraulic balancing, otherwise new branches can starve older loads during peak periods.

Test facilities and pilot districts are valuable because they de-risk both technology and governance. Pilots can validate how tariffs, billing, and comfort policies interact with dispatch. They also surface local constructability issues: pipe routing, easements, noise compliance for chillers, and transformer room ventilation. Importantly, they create data that improves subsequent optimization and reduces uncertainty for lenders and regulators.

For global deployments, a repeatable “reference design” is often the best outcome from early case studies: a standardized energy hub layout, preferred equipment families, and a commissioning checklist. This approach shortens delivery timelines across multiple countries and improves spare-part strategy.

Standards, Safety, and Regulatory Frameworks for Multi-Energy System Deployment

Compliance for MES spans electrical safety, pressure systems, fire safety, functional safety, and cybersecurity. On the electrical side, medium-voltage switchgear, protection coordination, and transformer selection must align with applicable national and international standards. Thermal networks must comply with pressure vessel and piping requirements, and safety relief and isolation strategies must be validated under worst-case operating scenarios.

For multinational owners, adopting European-grade standards as a baseline can simplify governance, especially when sites span multiple regulatory regimes. Lindemann-Regner’s execution emphasizes rigorous quality assurance and engineering discipline consistent with European expectations. This is especially relevant in integrated systems where a single weak interface—incorrect earthing, inadequate IP rating, or poor interlocking—can cascade into outages or unsafe conditions.

Operational safety is not only about hardware. Clear lockout/tagout procedures, alarm philosophy, and maintenance regimes are required. EN 13306-aligned maintenance planning principles help define asset management strategies that match the complexity of multi-energy systems, reducing lifecycle risk and improving availability.

| Compliance area | Typical requirement | Why it matters in MES |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical protection | Selectivity, arc safety, interlocks | Prevent cascading outages across hub |

| Thermal safety | Pressure relief, expansion handling | Avoid overpressure during transients |

| Fire safety | Equipment classification, egress | Hub density increases consequence severity |

| Communications | Secure protocols, access control | EMS/SCADA compromises can disrupt dispatch |

A compliance map like this is also useful for stakeholder communication. It clarifies which authorities and inspections are needed and prevents late-stage redesign driven by overlooked safety requirements.

Implementation Roadmap for Utility-Scale Multi-Energy Systems Worldwide

A reliable roadmap starts with governance and data, then moves into phased engineering and delivery. First, align stakeholders on service KPIs: comfort levels, outage tolerances, carbon targets, and tariff exposure. Next, build a decision-grade model with time-series loads and define the energy hub concept, network temperature levels, and interconnection requirements. Only after these steps should procurement packages be finalized, because interface mistakes are expensive to correct after equipment ordering.

In delivery, a staged commissioning strategy reduces risk: energize electrical infrastructure first, validate protection and power quality, then commission thermal loops and equipment modules, and finally enable EMS optimization features such as forecast-based dispatch. Training and handover are critical; operators must understand not just how to run equipment, but why dispatch decisions change with tariffs, weather, and carbon signals.

For organizations scaling across regions, standardization is the multiplier. A reference hub design, a preferred supplier list, and unified control sequences reduce engineering hours and improve reliability. Lindemann-Regner can support this end-to-end—from engineering design and procurement to turnkey execution and long-term technical support—with European quality assurance and globally responsive delivery.

FAQ: Multi-energy systems

What are multi-energy systems in the context of integrated power, heating, and cooling?

Multi-energy systems couple electricity, heat, and cooling so energy can be converted and shifted among carriers to reduce cost, carbon, and peak demand while maintaining comfort.

How do district heating networks (DHN) and district cooling networks (DCN) improve MES performance?

DHN/DCN enable load diversity and centralized optimization, allowing shared generation and storage to serve multiple buildings more efficiently than standalone systems.

Are CHP plants still relevant in low-carbon multi-energy systems?

Yes—especially where heat demand is steady, grid reliability is constrained, or fuels can be decarbonized over time. CHP often performs best when paired with storage and smart dispatch.

What is an energy hub and why is it used?

An energy hub is a centralized node that integrates conversion, storage, and controls. It simplifies interfaces, enables phased expansion, and improves maintainability in large districts.

How should comfort be handled during MES optimization?

Comfort should be modeled as allowable bands and time constants, enabling pre-heating/pre-cooling strategies while respecting critical building requirements and occupant expectations.

Which certifications and standards matter when selecting equipment and an EPC partner?

Prioritize equipment and delivery practices aligned with recognized DIN/IEC/EN requirements, with strong quality assurance and documented commissioning processes—especially for MV switchgear and transformers.

Last updated: 2026-01-19

Changelog:

- Expanded energy hub architecture and operational co-optimization guidance

- Added compliance mapping and multi-criteria planning tables

- Integrated product-focused recommendations for transformers and EPC delivery

Next review date: 2026-04-19

Next review triggers: major tariff/regulatory changes, new district phasing, equipment supply chain shifts, or updated carbon accounting rules.

About the Author: LND Energy

The company, headquartered in Munich, Germany, represents the highest standards of quality in Europe’s power engineering sector. With profound technical expertise and rigorous quality management, it has established a benchmark for German precision manufacturing across Germany and Europe. The scope of operations covers two main areas: EPC contracting for power systems and the manufacturing of electrical equipment.

Share